Which foods make a diet balanced, and more importantly, in what quantities should we consume them to maximize health benefits? Today, I begin a series of three articles in which I will summarize the fundamental principles of healthy eating, whether Mediterranean, Nordic, vegetarian, or vegan.

What Is Meant by “Diet”?

Before we get started, it’s useful to clarify what the term “diet” means in the scientific world. Unlike its common usage, it does not necessarily refer to a restrictive regimen aimed at weight loss. In fact, most of the time, it refers to a normocaloric diet, which provides exactly the amount of energy needed to maintain a stable body weight without causing weight gain or loss.

Of course, there are also hypocaloric and hypercaloric diets, used respectively for weight loss or weight gain. These regimens must always be prescribed and monitored by a specialist to ensure their safety and effectiveness.

In this article, I will discuss diets as normocaloric and non-restrictive eating patterns.

Balanced and Optimal Diets

A balanced or optimal diet is one that provides all the necessary macro- and micronutrients in the right amounts while minimizing harmful nutrients and substances, promoting health and preventing disease.

Despite cultural and dietary differences, when comparing the nutritional guidelines of various countries and scientific organizations, we notice far more similarities than differences. How is that possible? The answer is simple: epidemiological studies converge on a fundamental principle.

Any dietary pattern that preserves health and prevents chronic diseases must be based on unprocessed plant foods. The only variable is the percentage of animal products, which can range from 0% to 20%. For this reason, all these diets are classified as plant-based.

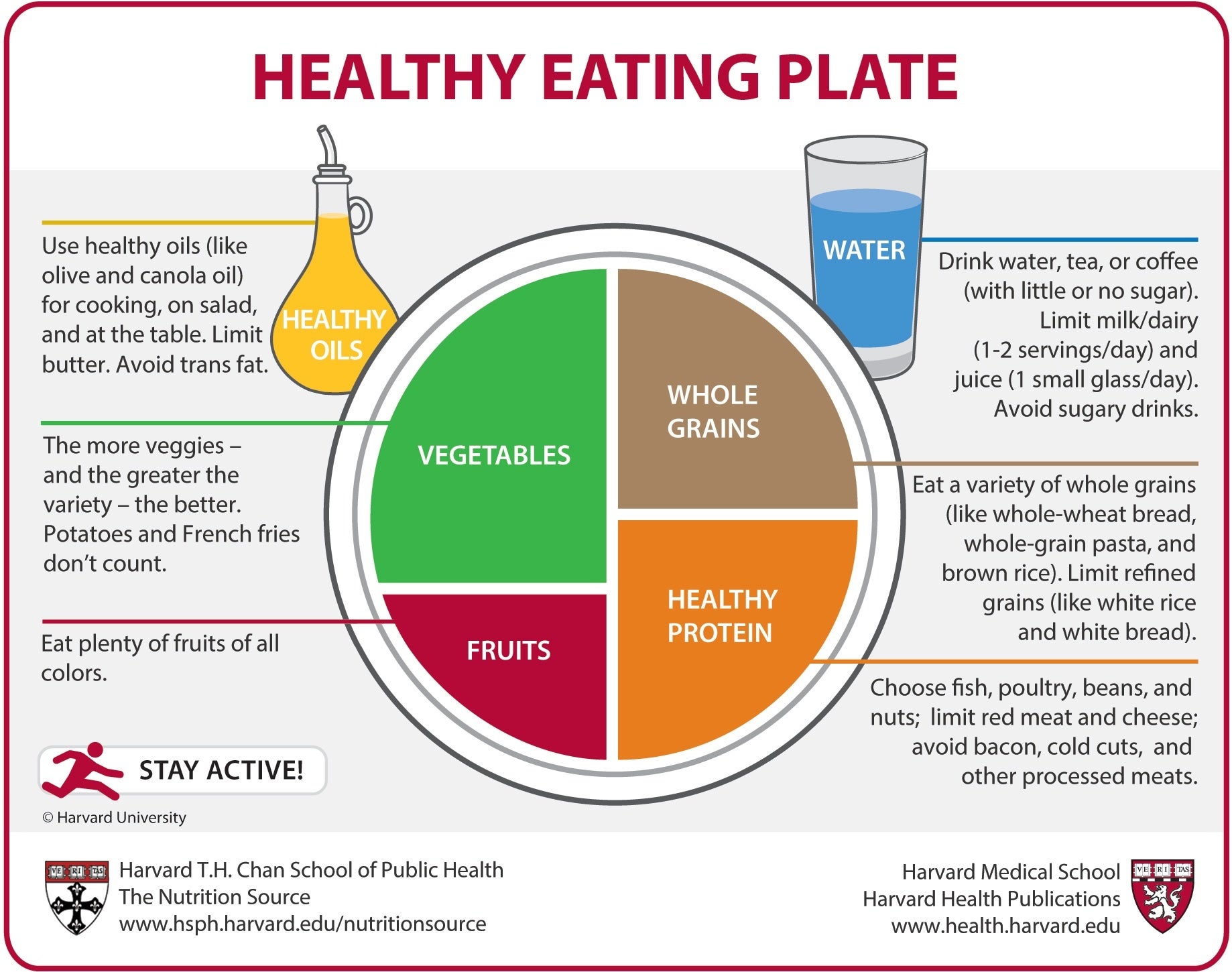

Before diving into each specific diet, here is the famous Harvard University Healthy Eating Plate, which provides a clear visual guide to structuring balanced omnivorous meals. Click the link below the image for more details.

Copyright © 2011, Harvard University. For more information about The Healthy Eating Plate, please see The Nutrition Source, Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, www.thenutritionsource.org, and Harvard Health Publications, www.health.harvard.edu.

Copyright © 2011, Harvard University. For more information about The Healthy Eating Plate, please see The Nutrition Source, Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, www.thenutritionsource.org, and Harvard Health Publications, www.health.harvard.edu.

Mediterranean Diet

It is one of the most widely discussed diets worldwide, thanks to its numerous health benefits compared to the so-called Western diet, which is characterized by a high intake of animal products, processed foods, and sugars.

But what does the Mediterranean Diet truly consist of? Is living in Italy or Greece enough to follow it? Or is eating at an Italian restaurant occasionally sufficient? Of course not. Unfortunately, today adherence to this diet is very low, even in the countries where it originated.

History of the Mediterranean Diet

Let’s start with the history. The concept of the Mediterranean Diet was introduced by the renowned American physiologist Ancel Keys after his studies on the correlation between diet and mortality. He named them the Seven Countries Study, as they involved 16 cohorts (groups of people from the same geographical area) across seven countries.

Keys and his collaborators discovered that mortality rates in Japan, Greece, and Italy were significantly lower compared to those in Finland and the USA, where the risk of cardiovascular diseases was about 20 times higher.

Analyzing local diets, they found that in these countries, food intake consisted of 85–95% plant-based foods, mostly unprocessed.

It is important to note that these cohorts were located in rural areas and mostly included farmers, who followed this dietary pattern often due to economic necessity. In urban centers and among wealthier populations, however, the diet was already quite different, and mortality rates were higher.

Mediterranean Adequacy Index (MAI)

Among the key investigators alongside Keys was Flaminio Fidanza, a distinguished Italian researcher who was later appointed Honorary President of the National Institute of the Mediterranean Diet. Fidanza continued the research and published several follow-up studies over the years. Together with his wife, Adalberta Alberti-Fidanza, he developed a score to assess adherence to the true Mediterranean Diet: the Mediterranean Adequacy Index (MAI).

The Mediterranean Adequacy Index (MAI) is calculated as the ratio between the total percentage of energy derived from typically Mediterranean foods and that from non-Mediterranean foods.

Among the typically Mediterranean foods were considered: cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruits, fish, olive oil, and red wine.

Among the non-Mediterranean foods: meat, dairy products, eggs, animal fats, margarine, sugar, sweets, and sugary beverages.

A higher MAI indicates greater adherence to the Mediterranean Diet.

Quantities of Plant and Animal Foods Consumed

It is interesting to note that the same study reports the average quantities of different food groups consumed in Nicotera, one of the Italian locations, included in the study, at the beginning of the study in the 1960s. Below, I summarize these data, summing up all animal and plant foods and adding the average quantities consumed by farmers in the Crete cohort, Greece, taken from another follow-up study.

| Cohort | Animal Products (g or ml/day) | Plant Products (g/day) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotera, Italy | |||

| Men (20-59 years) | 163 | 982 | |

| Women (20-59 years) | 119 | 734 | |

| Crete, Greece | |||

| Male farmers | 91 | 1285 |

Animal Products: meat, fish, milk, cheese, eggs. Plant Products: cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruit (excluding fats, wine, and sweets).

It is clear that the dietary pattern underlying the concept of the Mediterranean Diet was based on unprocessed plant foods, with only a minimal inclusion of animal products.

Follow-Up Studies of the Seven Countries Study

The same study that followed the farmers of Crete compared their diet in 1960 and 2005. It was found that the vast majority no longer adhered to the Mediterranean Diet, leading to an increase in various cardiovascular risk factors and beyond.

What exactly changed in their diet? The average daily quantity of animal foods increased from 91 g to 218 g, with a significant rise in meat, fish, and cheese, while the intake of unrefined plant-based foods significantly decreased, dropping from 1285 g to 752 g.

Moreover, numerous further studies have been conducted. In one of the most recent, the relationship between the MAI and cardiovascular mortality after 50 years was analyzed. Among the top three with the highest MAI and the best survival rates were both Japanese towns included in the study and one located on the island of Corfu, Greece.

Protective Components Against Cardiovascular Diseases

To conclude, I will mention a major 2018 meta-analysis that reviewed all prospective cohort studies on the Mediterranean Diet published up to that point. It analyzed which components of the diet were positively associated with all-cause mortality and which had a negative association.

It was found that higher consumption of cereals, fruits, and vegetables was linked to a lower risk, while higher consumption of meat and dairy products was associated with an increased risk.

Discover more:

Benefits and Key Foods of the Nordic Diet