Undoubtedly, one of the most frequently asked questions in human history is whether it’s possible to never grow old. Of course, we’d all love that but it’s clearly impossible. What we do know today, however, is that lifestyle has a major impact on the aging process. Let’s take a look at what these processes are, and how diet influences them.

Longitudinal and Cohort Studies

Before diving in, here’s a quick overview of the main types of studies underpinning much of what we know in this field.

Among the most widely used in medicine are prospective longitudinal studies, observational research in which a group of people is followed over time to gather data on how certain factors affect the onset or progression of disease.

A subset of these is cohort studies, which follow one or more groups with different lifestyles or exposures (for example, smokers and non-smokers) over time, comparing disease incidence between the groups. From this, researchers calculate the risk associated with each factor.

Naturally, this type of study is widely used in epidemiology and applied medicine, especially in relation to so-called NCDs, non-communicable diseases. These include cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and obesity, which are not caused by infections but by lifestyle and dietary factors. Such studies are crucial, as these conditions typically develop over several decades.

That said, it would be impossible to summarise all the evidence here, but what we see is that the vast majority of studies point in the same direction.

Dietary Patterns and Aging

Today I want to focus on a single longitudinal study published in February 2025 in the journal Nature Medicine. It was conducted by researchers from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who analysed data from two large cohort studies: the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, collected between 1986 and 2016.

They examined the link between adherence to eight different dietary patterns and healthy aging, looking at cognitive, physical, and mental health, as well as life free from chronic diseases up to age 70.

Among all dietary patterns analysed, the one most strongly associated with healthy aging was the AHEI.

The Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010) is a tool developed to measure diet quality in relation to chronic disease risk.

It assigns scores from 0 to 10 to 11 dietary components, for a maximum of 110 points. The closer a diet is to what’s considered healthy, the higher the score.

Healthy components (higher score with greater intake) include:

- Vegetables (excluding potatoes)

- Fruit (excluding juice)

- Whole grains

- Legumes

- Nuts

- Polyunsaturated fats

- Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA + DHA)

Components to limit (higher score with lower intake):

- Sugary drinks and fruit juices

- Red and processed meat

- Sodium (excess salt)

- Trans fats

- Alcohol

Participants with the highest adherence to this index had between 86% and 124% higher odds of aging healthily depending on the age threshold used (70 or 75 years).

Among all aspects of healthy aging, AHEI showed the strongest associations with preserving physical function and mental health.

These associations were independent of other lifestyle factors like physical activity, smoking, and body mass index (BMI).

Aging Mechanisms

So what causes aging? Today we know it’s the result of multiple processes, but I’ll briefly mention two areas that are currently the focus of extensive research: telomere shortening and epigenetic processes.

What Are Telomeres and Why They’re Called the Biological Clock of Our Cells

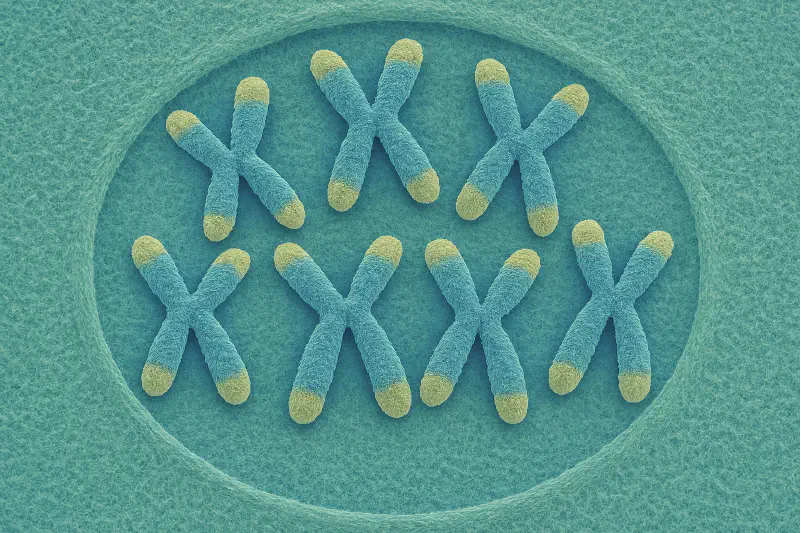

Telomeres are repeated DNA sequences at the ends of all chromosomes, which “wear down” slightly with each cell division. You can think of them like the erasers on top of pencils that wear down after a while.

When telomeres become too short, the cell stops functioning properly and enters apoptosis, a natural form of programmed cell death. Otherwise, if something in the mechanism malfunctions, the consequences can be more severe, leading to chromosomal damage and cancer development.

In fact, several studies have found that most human tumors have significantly shorter telomeres compared to the surrounding healthy tissue. Unfortunately, over time, cancer cells can acquire multiple mutations that enable them to reactivate the enzyme that elongates telomeres, telomerase, thus becoming immortal.

You can imagine the enormous scientific interest this has sparked. Naturally, the next big question was: what factors influence telomere shortening?

How Diet Affects Telomere Length

Numerous studies have investigated this, but I’ll focus on a 2020 systematic review, which analysed the main findings up to that point.

While results weren’t entirely consistent, higher consumption of vegetables, fruits, legumes, fibre-rich foods, and coffee was associated with longer telomeres or had a neutral effect in some studies.

Researchers also looked at the dietary patterns of the Mediterranean Diet, AHEI, and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) and found protective or neutral effects on telomeres.

In contrast, a high Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) was linked to shorter telomeres. I’ll explore this in more detail in an upcoming article, focusing on which foods are more or less inflammatory.

Epigenetic Mechanisms of Aging

We’ve all learned in school that our genome doesn’t change over the course of life. But today, there’s growing interest in epigenetics (from the Greek epi, “above”), meaning the processes that “turn on” or “turn off” gene expression in response to specific stimuli.

As you can imagine, this discovery has revolutionised genetics. It’s a rapidly growing field that examines how age and exposure to environmental factors, including diet and physical activity, can alter gene expression.

Again, without going into too much detail, I’ll just highlight one recent study, probably familiar to some thanks to the Netflix series You Are What You Eat.

It’s an intervention study called the Twins Nutrition Study (TwiNS), conducted by researchers at Stanford University led by Christopher Gardner. They enrolled 22 pairs of monozygotic (identical) twins to rule out the influence of genetic factors.

Each twin in a pair was randomly assigned to one of two diets: one vegan and one omnivorous, both balanced. Numerous parameters were measured at the beginning and end of the 8-week study. So far, three scientific articles have been published, focusing respectively on metabolic improvements, epigenetic changes, and microbiome modifications.

The second article assessed various epigenetic markers, along with effects on specific organs and systems. The vegan group showed a significant reduction in epigenetic aging acceleration.

Furthermore, by the end of the study, the vegan twins had significantly longer telomeres than their omnivorous counterparts, while no differences were observed at baseline. This supports the idea that the telomere lengthening was a direct effect of the diet.

I’ll conclude by saying that this is a topic as complex as it is fascinating, one that will require much more research and exploration in the future. With this brief overview, I hope to have made you reflect on how deeply our daily food choices can influence our biological clock.

Discover more: